Make Believe Melodies’ Favorite 2018 Japanese Albums: #10 – #01

#10 Suiyoubi No Campanella (Wednesday Campanella) Galapagos

I shouldn’t be surprised by anything KOM_I of Suiyoubi No Campanella does, yet back in the early days of summer I watched slack-jawed as she left the stage at a quaint venue near Mt. Fuji and wandered into a field that had been set on fire sometime during the preceding two hours. This group has upended expectations for years now and wowed me enough last year en route to them taking the top spot in the 2017 list, but they always find a way to keep things interesting — even if it involves burning swaths of grass — and add to their own sonic world.

Galapagos spent a little time finding the trio revisiting familiar formulas — see the rumbling mythology-gone-dance-pop of “Three Mystic Apes,” as close to boilerplate Suiyoubi No Campanella as one can get — but mostly captured a group poking around and finding their voice (litarlly), all in search of what direction to pivot next. But even these tests proved, by the end of 2018, to be among the year’s finest. The big development is a risky one — KOM_I, whirling dervish incarnate, drops rapping in favor of singing across all 36 minutes here. But it results in highlights such as the refined theatrics of “The Bamboo Princess” and the understated shuffle of “Minakata Kumagusu,” a song seeing how few parts can be used to assemble an emotionally affecting hook. Half-speed dreampop collaborations with French art types rubbed shoulders with mutations on classic rock stomp. Even the two ballads closing out the album, what felt like noble failures at first brush but have grown into interesting detours for a project operating as far away from soaring end-credit J-pop as possible. Part of Galapagos’ appeal lies in how its a document of a group in flux…I doubt Suiyoubi No Campanella will sound like this a year from now, and they might settle on one specific path to go. But this is them moving in eight at once, surrounded by flames and an endless pool of ideas.

#9 Foodman Aru Otoko No Densetsu + Moriyama EP

Foodman’s world continues to sound totally perplexing, but also familiar. These two releases inspire adjective and verb brainticklers, daring listeners to break out the thesaurus to describe individual noises. Nobody in Japan — maybe nobody anywhere, honestly — loves single sounds quite like Foodman, who constructs songs out of skittering vocal samples, the sound of soda being poured into a glass, stray guitar strums, flute sprays and whatever else tickles his fancy. If 2016’s Ez Minzoku was a technicolor gobstopper of glorious nonsense, Aru Otoko No Densetsu offers a little more space for meditation, less screams and creepy spoken word in favor of experiments in percussion (including a song called “Percussion”) and actually heart-tugging singing courtesy of Tokyo-based creator Machina. It’s still every bit as offbeat, but now it feels more graphed out on paper, even if done in crayon. The Moriyama EP offers a nice companion to that full-length, with Foodman going even deeper with beat experiments, from icy start-stop scronk on “Kishimen” to slow-burning meditations on “Mizuburo,” his longest offering of anything on these releases. Foodman has stepped up to become the modern artist best representing Japan’s experimental music community internationally, and he’s earned it. Get Moriyama here, or listen below.

#8 Koutei Camera Girl Drei New Way Of Lovin’

As the end of the decade looms, idol music in Japan finds itself in a strange place. This sub-section of J-pop started fragmenting right as the 2010s got under way, and with 2020 coming everything feels flipped. Despite English-language media’s continued use of them as a crutch, AKB48 feel fading (unless your metrics only revolve around sales, which…c’mon now) and focused on expanding across the continent. But Nogizaka46 and Keyakizaka46 are thriving, the latter in particular approaching what might happen if Yasushi Akimoto learned what “woke” meant. BiSH has become a legitimate A-list act, while Pour Lui is now a YouTuber. Maybe she’ll go virtual next? And then there’s this vast lower-middle space, full of acts repping all kinds of styles of varying quality. It’s all over the place, and free of big-picture narrative.

Which makes it all the easier to celebrate Koutei Camera Girl Drei, an outfit lurking somewhere in that great idol abyss creating some of the most vibrant music period in the country. If the aforementioned Koto album combs through junk culture and refashions it into a good time, New Way Of Lovin’ digs into dance styles predominately found in underground electronic communities across the archipelago (helping matters, the folks behind the boards hail from that world) and fashions it into a pop laserbeam. Critically, Koutei Camera Girl Drei don’t limit themselves to one gimmick — opener “No Limit Dance” weaves idol-appropriate “woos” into a four-on-the-floor chug, and from there zig-zags between all-together-now verses, raps, and a huge chorus where every elements criss-crosses. Like every idol group, the members themselves aren’t polished per se, but the trio central to this release cover any gaps with an energy that matches the techno speed run of “Toronto Lot (New Ver.)” and the aptly titled “Lonely Lonely Montreal (Trance Ver.).” They also cover half-speed melancholy (“Salad”), extra-hard idol fare (“Slowly World”) and pure delirium (“Harbor”). They’ve got a house style, sure, but the thrill comes in how the group expands on that central sound and isn’t afraid to branch out. The end result is the best idol release of the year, and a pop album that can go toe to toe with any.

Holding it back just a little? The fact it is a mini-album ahead of a full-length out in January. Geeeeeez, what is that going to sound like???

#7 Tsudio Studio Port Island

88Rising founder and CEO Sean Miyashiro recently told Japanese site Newspicks that the type of music out of Japan getting the most buzz internationally (or at least internet-ally) is city pop, and he thinks if an artist could use those attributes from the ’80s today, they might have something viable. Local Visions is way ahead of that. The thrill of watching this label come up in 2018 is mostly because nobody else released as much quality music under one umbrella, but also partially because few collectives have pinpointed what about Web-born nostalgia for the Bubble days is all about. The artists — Japanese or otherwise — working with them this year nail that these online visions are mirages, and that they shouldn’t be slaves to recreating the sounds of Tatsuro Yamashita, but rather using the past as clay to sculpt how they want.

As the year ends, Kobe artist Tsudio Studio’s Port Island sticks around the most in our head, offering both the sleekest re-interpretation of neon-glazed memories and a best foot forward. The city pop signifiers overflow, from shiny synth melodies to a seaside vibe complete with bird samples chirping away over guitar solos to saxophone baby. Take the most basic tracks here, set them against looping images of an anime woman dancing, and you’d have algorithmic gold. But Tsudio Studio isn’t settling for being locked in place, but rather using these familiar elements in a way that sounds nothing like city pop, or “city pop,” or even “new city pop” clogging the aisles at Tower Records. Sounds smear together, while Tsudio Studio’s own digitally manipulated voice peeling through the songs. City pop gets remembered for excess and cars, but it’s also about musicians using the latest developments in instrument technology to create a maximalist type of sound drawing on the past but sounding nothing like it. Port Island updates this for the digital age, using all kinds of computer tricks and internet-born touches to build on what came before. It isn’t looking back, but moving forward. Get it here, or listen below.

#6 Pasocom Music Club Dream Walk + Condominium — Atrium Plants EP

Look, I could pretty much just repeat what I said above about Tsudio Studio to talk about the whole Pasocom Music Club project — or I could direct you to last year’s blurb, which similarly touched on the fact that these guys are playing around with online nostalgia in interesting ways. It continued on these two releases as well, but instead of rehash it, let’s celebrate just how fucking catchy Pasocom’s music has gotten. If major labels aren’t flooding their inboxes with remix requests and production jobs after Dream Walk, I don’t know what’s wrong with everybody. “Virtual TV” turns talk-box sing-song into a pogoing earworm demanding replays, while “Oldnewtown” turns those same manipulated vocals into a new layer on a straightforward pop slink. “Inner Blue” shows they can also slow it down a bit, and reminds of their melancholy streak too. Along the way, Dream Walk fits in rave outs, acid house meltdowns and chill-out digi-sax tracks. Condominium — Atrium Plants EP, released a few months later, offers a better snapshot of how their live sets go — I saw them this summer, and as they noted at the end, paraphrased, “whoops, we didn’t play anything from Dream Walk” — by leaning into their more rollicking floor-filling tunes, flashing tropical breakdowns and acid-sloshed rumblers. Don’t let the potential thesis material on gazing towards the past scare you — Pasocom in 2018 was all about creating some of the year’s catchiest songs. Get Condominium — Atrium Plants EP here, or listen below. Dream Walk, on streaming services!

#5 Xinlisupreme I Am Not Shinzo Abe

Five words. Most artists in 2018 can’t be this direct with their politics — meaning is clouded in metaphor or left as clues for listeners to pick apart like they are watching True Detective or whatever. Or worse still, there is no meaning, but people hoist views onto works because, welp, welcome to 2018. It sucks! So keep it simple, and get to the point. Xinlisupreme sums up their entire view of contemporary Japan elegantly and with unrelenting guitar feedback making it crash in even harder. “I Am Not Shinzo Abe.” Perfect.

What makes Xinlisupreme’s first album since 2002 such a force isn’t just that it carries political overtones. Really, outside of the title track and the reprise of the title track featuring a child repeating said statement, there isn’t any direct messages…mostly because there aren’t any direct words, every syllable wrapped up in guitar squall. Noise somehow gives way to mish-mashed melodies where snippets of voices and drums break through the frenzy to form beautiful little moments amongst the crush. That Xinlisupreme could follow up Tomorrow Never Comes with something every bit as harsh but jubilant is celebration enough.

But it isn’t just that. I Am Not Shinzo Abe is 16 years of lived life and national calamities — 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, Fukushima Daiichi, the big protests in the last few years standing out — synthesized into music. It’s an artist who told me he felt the responsible to speak out doing just that, but in a way far more compelling (and listenable) than the audio equivalent of a Twitter thread. And it’s bound to be just as strong years from now. Get it here, or listen below.

#4 Cero Poly Life Multi Soul

Trio Cero basically accelerated Japan’s fascination with smoothed-out sounds with jazzy elements stirred in with 2015’s “Summer Soul,” a contemporary Tokyo cruise with the windows rolled down and not a cloud in sight. This one song got big enough to warrant an appearance on SMAP’s cooking-slash-music-show, exposing it until millions more. And in the years since, all kinds of bands have come up operating in the same mode, spurring something a few dubbed “new city pop” and which groups rode to even bigger fame. Cero, a group that spent nearly a decade pivoting from Grizzly-Bear-ish rock to a kind of millenial Shibuya-kei, could easily have locked into this style en route to some NHK features.

But they didn’t, and with Poly Life Multi Soul they made their masterpiece. Cero used their newfound capital from success to load up on horns, keyboards, back-up singers and whatever else they could nab to create a twisty, turvy album that’s complex but never snooty. They explore polyrhythms and drew inspiration from music cultures from around the globe, but it never feels shut off or like a museum — right in the middle of this thing, they invite you to a “Buzzle Bee Ride,” an imagined dark ride anyone can board. Poly Life is downright celebratory, pure tipsy pleasure on “Floating On Water” and all the drama of a movie short on the rollicking “The Kid From Lethe” (on top of all this, Cero probably put on two of the best shows I saw all year, one where they not only pulled all this off, but offered up a party atmosphere for all to get lost in). If there’s ever an argument against settling, here it is.

#3 Mom Baby Like A Paperdriver + Playground

This year might have been a rejoinder to the idea of the internet as digital utopia, but if you’re looking for a positive, a new generation of artists have established themselves as completely uninterested in following established rules. This isn’t a revolution — in Japan, netlabels were one of the first great examples of online destinations treating genre like YouTube recommended-video sidebars, just all over the pace — but man, these new kids feel so natural doing it. Saitama oddball Mom delivered two albums this year delighted to just jump all over the place, and in the process hit on novel ideas that other artists in the country focused more on just one thing can’t get down. Baby Like A Paperdriver came out near the start of 2018 on Ano(t)raks, and probably rushes my top ten all its own. Songs here go from hip-hop-scotch (“Cinema”) to something closer to turn-of-the-century indie-rock (“Man After Man”), before swinging into singer/songwriter acoustic whisperings (“Gypsy”). Rap does end up being his dominant style, but done in a way that’s totally alien from anything else happening in Japanese hip-hoop…like, anyone dreaming up something approaching “Tokyo Instant Babys,” let me know. Get it here, or listen below.

Every week, I opened up Apple Music and was greeted by some “new artist of the week” that was just a bad rapper saying “swag” and then a food item you can buy at Family Mart. Imagine my thrill this fall when Mom’s Playground popped up in that space — here was an artist not trying hard, but rather just following their own strange, internet-honed freedom to create something all their own. Funny enough, the best song on this proper debut, “That Girl,” is no longer included in it (sample problems?), which is a shame, but Playground features plenty of other highlights to make up for it. The sparse “Natsuno Maho” allowed space for Mom to deliver his springiest and sweetest verses, while “Skirt” flashes pop potential mixed with splashes of rock. It’s a playful showcase of what happens when you reject genre borders and just have fun. Excited to see even more youngsters give this a go.

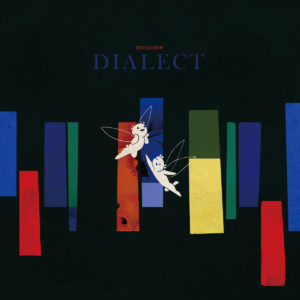

#2 Metome Dialect

Memories can be a tricky thing. Japanese music spent 2018 looking back, celebrating superstars calling it quits or trying to recall tunes from better economic days. But not all nostalgia is equal, and some of it ends up feeling more personal, more intense. There’s a certain kind of electronic music that, today, feels like it only exists as the soundtrack for YouTube videos by mannequin-like influencers, or the intro theme to a game app nobody plays anymore. Trends come and go, but maybe this one — a sort of loose-limbed, hyper-chopped style once prevalent on SoundCloud (remember the heyday of that site?) — struck more of a personal chord.

It haunts Metome’s Dialect, an album where this familiar high-energy style fades until only something faint remains. That Osaka producer would know best — he came up at the same time his home city and the surrounding Kansai region enjoyed an electronic music fertile period, spurred in part by the INNIT parties that helped shine a light on Seiho, Madegg, Avec Avec, And Vice Versa…list goes on. Here’s where the personal comes in — I lived in Osaka around that time too, and was able to go to a fair amount of these shows at the basement Nuooh, and really see this community flourish. Lots of great music came from this period, including Metome’s Objet, which typifies a style built around sliced-up vocal samples and tight arrangements shooting all over the place. For a second, this felt like something about to go supernova, and it kind of did — Seiho tours internationally and works with big names, Avec Avec remixes Johnny’s artists, this sound slowly creeped towards the mainstream. But something was lost, even if it’s hard to pinpoint.

Dialect isn’t specifically about any of this, but it’s tough for me to listen to this and not hear that recent history drifting through each track. Vocal samples return, chopped up like before, but slower and a little saggier. “Palm” features the same machine-generated percussion and synth washes, but rather than being joyful they slump forward. “Koala” features a nice rhythm and some acid-house touches in the back, but even it feels building towards a sigh. It would be a downer if Metome weren’t so good, maximizing space so that every detail delivers an emotional punch, and making later drone-leaning cuts like “Myrtle Family” and the more spacious ambient exercise “Breeding Tank” welcome interludes from the memory decay around it. Part of this one’s charm for me is how it memorializes something that wasn’t far removed but feels so far away now, kind of an ode to all artistic communities that inevitably pass on to the next. Yet buried in there is also a lot of joy for the music to — as downbeat as “Sathima” or “Passage” get, Metome lets them rumble, a reminder of all the outright fun those times had — and how much they inspired the future, even in small ways. Get it here, or listen below.

#1 Haru Nemuri Haru To Shura

Music sure could feel worthless in 2018. Forget any “real world” happenings that cloud out art — all you had to do was look at how it was covered by publications, how it was reduced to Moneyball statistics via streaming services, how it often felt like a Lego brick in a bigger brand picture for YouTubers or Instagram people. Maybe that has always been the case, but this year was all about everything feeling accelerated and extra crushing. I got pretty cynical about it all this year. But sometimes you just need to listen to someone who treats it like the most important part of their life.

Haru Nemuri spends large chunks of Haru To Shura finding escape in music itself. She seeks refuge in distortion on “Narashite,” a number also concealing a reference to a Supercar album offering plenty of just that. She feels alive on “Underground,” an ode to slipping away to what sounds like a live show. And it ends up being the only way she can grapple with the reality of being alive, of having to deal with death and conflict way out of her control. She’s not trying to find answers or even change the structure of things — she just wants somewhere to retreat to when it all makes you want to scream, or to turn to it when that’s really all you can do.

This list and other things I’ve written have spent a lot of time focusing on nostalgia and looking back, but this year in Japanese music was also all about looking forward. Look over this blog’s favorites and you’ll see no shortage of young artists who have come up in a digital world, who disregard genre and just create whatever sounds best to them. Haru Nemuri personifies this perfectly — a kid raised on mainstream J-pop getting into slightly less mainstream (but still, like, first-floor Tower Records located) J-rock who then dips into American indie acts like Yeah Yeah Yeahs thanks to the Web. And from there, she encounters beat music, dance and hip-hop among others, all of which become areas she can play around in and draw from.

The musical splendor of Haru To Shura was evident pretty much right away. “Make More Noise Of You” almost serves as a red herring, all barreling-forward guitar riffs and chugging beat. But then her voice comes in, and it’s more rap than rock delivery…at least until it starts quivering as she ups the emotion. From there, Haru Nemuri creates spaced-out beats to talk-sing over on “Underground,” nervy blown-out digi-pop on “Nineteen,” and flat-out rippers on songs such as “Lost Planet.” Her voice goes in all kinds of directions, from whisper to literal breakdown-worthy scream, and she constantly samples and loops her own syllables to create new tracks to trample all over. On the title track, her voice splits into mini-Haru-Nemuri’s and slowly speeds up alongside the song after the click of a button…before Chipmunking into oblivion, only to be brought back by some uninterrupted words. It’s jarring, and a sign Haru Nemuri’s world features its own type of magical realism.

Like albums by Mom or Tsudio Studio or even Koutei Camera Girl Drei — or even artists such as Suiyoubi No Campanella and Oomori Seiko — it’s refusal to settle for just one style made Haru To Shura stand out in a year where being correctly slotted in the right playlist could pay big (read: a few hundred dollars) dividends felt exciting, and that Haru Nemuri pulled it all off with songs as downright catchy as these makes it all the better. That Haru To Shura ended up being the 2018 Japanese album to actually travel and charm critics is one of the year’s most lovely surprises. I hate calling anything the “future” of…well, anything…but what Haru Nemuri does is definitely how artists of the future are going to approach music (and, globally, that’s already happening, and only going to get more commonplace).

But it wasn’t a personal lock for this space in the first half of the year, and really it took that cynical feeling ebbing around inside my head to really make this one click (talking to Haru Nemuri herself helped a lot too). As deflating as things could get, dipping back into Haru To Shura reminded of the thrill music can bring, whether from small details or moments on songs such as “Sekai O Torikaeshite Okure” or “Yume Wo Miyou” where her voice just can’t hold itself back anymore and lets loose. Again, no answers and no solutions — just feeling, in all its rawness.

And that’s ultimately the thrill that keeps coming through in every listen of Haru To Shura. All that talk about digital natives taking over and tearing down genre barriers sounds nice, but borders on tech talk, the same cynical babble that makes me get all grumpy about “the state of music today.” But Haru Nemuri reminds that whatever form the music takes, whatever inspiration it draws from, the emotion powering it can still come through loud and clear. I needed to hear that — and heard it done so creatively and forcefully — this year, and that worth makes me feel confident this is the album I’ll come back to most when thinking about 2018